Every sixty seconds in the Niger Delta, 600 Mscf of natural gas is flared, releasing an estimated 12 tonnes of toxic gases into the environment. Gas flaring in Nigeria is a major contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions and by extension global warming and climate change. Its impact on surrounding communities, however, remains its most devastating effect.

Some progress has been made in past the few years, but Nigeria still flares gas at an unprecedented scale. Even as the cost to communities is intolerable, the gas flares of the Niger Delta remain – stubbornly roaring their defiance as they light up the night sky.

Almost 60 years since the first flare was fired, the economic benefits that have warranted the existence of these flares remain as elusive as the environmental justice sacrificed to keep them. Perhaps it is time Nigeria stopped burning its proverbial candle at both ends and reformed its approach to exploiting its petroleum resources.

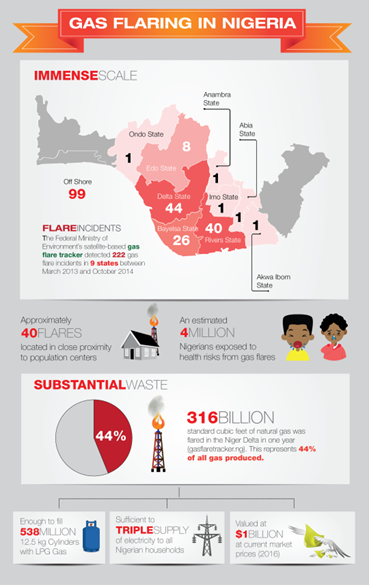

Since 1958 when Shell D’Arcy commenced commercial production in Oloibiri, Bayelsa State, the number of gas flares in Nigeria have grown at pace with oil production. Today, there are an estimated 100 active gas flares dotting the landscapes of the Niger Delta.

While the government has repeatedly attempted to curb the practice, putting an end to gas flaring in Nigeria has remained an elusive goal. The failure to end gas flaring has resulted in significant health and environmental costs to communities in the Niger Delta.

Associated gas is a by-product of the extraction of crude oil. It is released from oil wells in the process of pumping crude oil to the surface. Often seen as more of a nuisance than an economic resource, gas is burnt as it reaches the surface in a process called flaring.

For energy starved Nigeria, the flaring of gas presents an immense opportunity cost. Refined associated gas has significant economic value. As a cleaner source of energy than other fossil fuels, it can replace firewood which is currently the predominant fuel for cooking – reducing the pressure on our already depleted forest resources. Its application in power generation is indispensable, particularly for Nigeria where 18.6 million households go without electricity. Besides its application as a fuel, it can also be used as feedstock for fertilizer and petrochemical plants.

In addition to the substantial waste of scarce energy resources (an estimated loss of $1.5bn every year), gas flaring poses significant environmental and health risks to surrounding communities. Emissions from gas flares contain oxides of carbon, nitrogen and sulphur, particulate matter, black carbon soot, volatile organic compounds, toxic heavy metals and hydrogen sulphide. These noxious pollutants are associated with various respiratory, neurological, reproductive, cancerous and developmental diseases.

As toxic gases rise into the air, they interact with atmospheric moisture. The sulphur dioxide (S2O) and nitrogen oxides (NOx) dissolve to form sulphuric and nitric acid – which subsequently falls as acid rain. This results in increased soil and water acidity destroying waterways, animal and plant life. The net effect is that communities lose their environment, ecosystem diversity, livelihoods and their health.

A 2005 study by the Environmental Rights Action (ERA) and the Climate Justice Programme (CJP) estimated the impact of toxic air pollutants from gas flares on Bayelsa State. The study found that gas flaring from 17 locations in the state could be linked to an estimated 120,000 asthma attacks, respiratory illnesses in 4,960 children, 49 premature deaths and 8 additional cases of cancer every year (Gas Flaring in Nigeria: A Human Rights, Environmental and Economic Monstrosity - ERA & CJP 2005). These numbers represent only a fraction of the overall health impact of gas flaring on Niger Delta communities. An additional 35 flare sites are located in proximity to human habitations in five other states.

A 2005 study by the Environmental Rights Action (ERA) and the Climate Justice Programme (CJP) estimated the impact of toxic air pollutants from gas flares on Bayelsa State. The study found that gas flaring from 17 locations in the state could be linked to an estimated 120,000 asthma attacks, respiratory illnesses in 4,960 children, 49 premature deaths and 8 additional cases of cancer every year (Gas Flaring in Nigeria: A Human Rights, Environmental and Economic Monstrosity - ERA & CJP 2005). These numbers represent only a fraction of the overall health impact of gas flaring on Niger Delta communities. An additional 35 flare sites are located in proximity to human habitations in five other states.

Nigeria’s government is heavily dependent on oil revenue – deriving over 75% of its earnings from crude sales. Government is also the largest partner in joint venture oil production operations (JVs) in the country. Compared to the significant investment required to utilize gas cleanly and responsibly, flaring represents a cheap and dirty approach to disposal of associated gas while keeping the crude flowing. Subsequently, the choice between maximizing oil revenue and responsible oil extraction presents a perpetual conflict of interest for government.

It is this conflict of interest that has hindered effective environmental regulation of oil production in Nigeria. Hence, despite the prohibition of gas flaring in Nigeria since 1984, prescribed penalties are practically unenforceable since government cannot punish itself.

Nevertheless, sustained pressure from international and community activists has forced the Nigerian Government to incrementally improve its environmental performance. Government reports indicate that gas flaring has dropped from 50% to 12% of total production in the past 6 years, although independent reports suggest that actual reduction is significantly less. Improvements have been driven by increased investment in gas utilization infrastructure guided by the Gas Masterplan developed under President Umaru Musa Yar’Adua in 2007.

These improvements are laudable, but more still needs to be done. Recent improvements have been dependent on favourable market conditions and the availability of off-take infrastructure. With the current low oil prices leading to a significant reduction in oil and gas investments, progress has stalled.

But the real costs of gas flaring are human and environmental. Consequently, the impetus to eliminate gas flaring cannot be left to market forces. Government must urgently conduct an independent environmental impact assessment on all active gas flares in Nigeria. The impact assessment will help inform the decision as to whether the economic benefit of keeping those flow stations operational justifies the cost of the associated flares to the communities and their environment.

After all, there can be no prosperity without peace, no peace without security and no security without justice. In Nigeria, we will do well to remember that the scope of justice includes environmental justice.

Amara Nwankpa is the Director of the Public Policy Initiative for the Shehu Musa Yar’Adua Foundation. The Foundation’s documentary “Nowhere to Run: Nigeria’s Climate and Environmental Crisis” – currently screening in cities across Nigeria – establishes the relationship between the lack of environmental justice and increasing climate-fragility risks in Nigerian communities.

Amara Nwankpa is the Director of the Public Policy Initiative for the Shehu Musa Yar’Adua Foundation. The Foundation’s documentary “Nowhere to Run: Nigeria’s Climate and Environmental Crisis” – currently screening in cities across Nigeria – establishes the relationship between the lack of environmental justice and increasing climate-fragility risks in Nigerian communities.