A major incentive for colonial rule in Nigeria were her natural resources and the wealth hidden beneath her soils, including large deposits of minerals strewn around the country. So alluring and wide spread were these deposits that it motivated the colonial government to amalgamate the territories now known as Nigeria for easier colonial management and transportation to Europe. Abiodun Baiyewu-Teru looks at the history of coal in Nigeria.

Coal was first discovered in Nigeria in 1909 at the Udi Ridge in Enugu by a British mines engineer, Albert Kitson. Kitson had been prospecting for silver. By 1914, the year of Nigeria’s amalgamation, the first consignment of coal made its way to the United Kingdom from the newly created ports at Port Harcourt.

By 1916, the Ogbete Mine was in full operation and in that year alone, it yielded 24,511 metric tons of coal. Over time, other mines sprang up in the region which became the modern day Enugu State. Coal production hit an all-time high of 790,030 metric tonnes before it faced a steady decline due to reasons discussed below, which resulted in many of the mines being abandoned. Currently Nigeria’s coal deposit is estimated at about 2.8 billon metric tons.

Coal for Rail

To manage the resources produced at these mines, the Nigeria Coal Corporation was incorporated in 1950. The core domestic market for coal production in Nigeria was its emerging rail system which depended heavily on the produce to power its locomotive engines. But with the sudden discovery of hydrocarbons in the late 1950s, the Nigerian Railway Corporation switched from coal to diesel powered energy. The Electric Company of Nigeria also converted its power generation from coal to diesel. The loss of these two big clients played a major role in the decline in coal production as the government did not think it feasible to continue to heavily invest in the sector. Besides, the recent discovery of crude oil at Oloibiri held the promise of greater revenue through exports for the newly independent nation. The Coal Corporation survived the onslaught of crude oil especially because it continued to enjoy a national monopoly on coal production.

The Nigerian civil war was another major factor in the decline of the Nigeria Coal Corporation. A number of the coal mines became inaccessible during the period and were abandoned. Most of the abandoned coal mines were never revived or reclaimed. Interestingly, two mines were commissioned during the civil war: One at Odagbor, which was later known as the Okaba coal mine, located in present day Kogi State, and the Biafra Coal Corporation in Enugu. Both were merged at the end of the war into the Nigeria Coal Corporation.

Attempts at mechanizing the mines in the late 70s and 80s failed, further plummeting production. Another concern in the 1980s and most of the 1990s was the poor management of the Nigeria Coal Corporation. The then military government had a perchance for randomly appointing personnel with little or no experience in management or without technical knowledge to manage public enterprises. The Nigeria Coal Corporation was no exception. With the appointment of a university professor who had no management experience to head the corporation, its further decline came as no surprise. The final blow was in 1999, when the Nigerian government sought to increase direct foreign investment in the country by privatizing the Corporation and opening the nation’s solid mineral market to large private investors. The strategy failed. With the withdrawal of support from the government, the Corporation lost its steam. It however remained in operation till 2002 before eventually shutting down. Unsuccessful in its privatization bid, the Federal Government in 2013 sold off some of the Corporation’s assets to the Enugu State government in order to offset outstanding debts.

Enugu, the Coal Capital

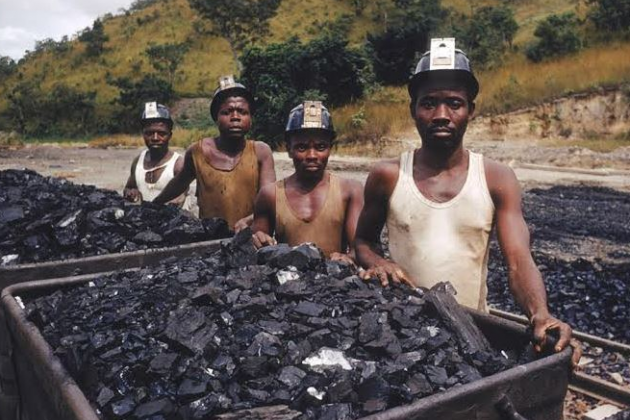

The discovery of coal in Enugu had a kaleidoscope of effects on the town and indeed the nation. For one, it contributed to the rapid development of the town and made it a commercial hub for the region. The wealth generated from coal was so strategic that Enugu became the capital of the Eastern Region in 1938. Its wide spread influence also led to the establishment of a thriving port at the area now known as Port Harcourt (which also became a city of reckon), to ship coal out of Enugu to Europe. Coal mining quickly spurred the growth of the population of Enugu with the influx of miners. The total number of miners working in the region jumped from 6,000 men in 1948, to 8,000 men in 1958.

The aftermath of the Iva Valley Massacre of 1949 played a prominent role in the national agitation for independence. The Iva Valley Massacre revolved around the miners’ strike of 1949 in which miners demanded better wages and conditions of service but was viewed by the colonial government administrators as confrontation and a covert call for independence.

Coal miners against colonial rulers

Historical accounts state that the coal workers, agitated by rising inflation and the failure of the management to recognize the Colliery Workers Union had started to demand for increases in their wages and the recognition of their union as far back as 1944. However, matters came to a head in November 1949 when the workers decided to embark on a work-to-rule strike to drive home their points: they refused to work for longer than the minimum required hours and operated strictly within the confines of their minimum deliverables and thus considerably slowed down the operations of several coal mines. Three days into the work-to-rule strike, the management attempted to sack 200 hewers. For several days the fired hewers occupied the mines so they would not be replaced by new recruits. In solidarity with their husbands, the miners’ wives protested at the colliery’s office destroying equipment and breaking windows. In response, the management called the police to disrupt the protests and in the fracas that ensued, some of the women were wounded. Even that event did not dislodge the miners. The tenacity and wide support for the protests led the colonial government to believe it was an insurrection with communist backing and that it was instigated by members of the Zikist Movement, who were agitating for national independence. It also feared that the protesters would steal the explosives from the mines and use them in terrorist attacks. It therefore dispatched 900 soldiers and policemen from the northern part of the country to dislodge the miners and secure the explosives. The ensuing standoff between the colonialists and the miners led to the killing of 21 and the grievous wounding of 51 unarmed miners by the Colonial Police. Historical records cite that Captain F.S. Philips, a colonial officer vexed by the striking miners’ solidarity chants, fired the first shot, which hit a hewer - Sunday Anyasado - in the mouth, killing him instantly. Another military officer joined Captain Philips in shooting at the protesters and in the aftermath of the ensuing mayhem, 21 miners were dead. These events became known as the Iva Valley Massacre and have become a reference point in the history of the labour movement in Nigeria. It also marked a tipping point in Nigeria’s quest for independence – a fact often lost in the formal teaching of Nigeria’s history.

The event catalyzed mass protests in other cities including Port Harcourt, Aba and Onitsha. According to political scientist Richard Sklar, “Historians may conclude that the slaying of the coal miners by police at Enugu first proved the subjective reality of a Nigerian nation. No previous event ever evoked a manifestation of national consciousness comparable to the indignation generated by this tragedy”.

Coal also managed to play a prominent role in Nigeria’s politics in the nation’s early years, post-independence. Having earned Enugu, its position as the Eastern Region’s capital, it subsequently became the short-lived strategic capital of Biafra, during Nigeria’s civil war with the Biafra Coal Corporation providing essential power to the Biafran struggle.

Coal economy at independence

Coal accounted for a sizable chunk of Nigeria’s revenue at independence and made a major contribution to the development of its national infrastructure. While there are no accurate records of the number of persons employed at the mines for the entire duration of its existence or its dependent economies, what we do know is that it was considered to have provided employment for a sizeable population of people and that the final demise of the Nigeria Coal Corporation impacted commercial activities in the city. As a mining town, Enugu attracted local, national and international migrants who worked at the mines and provided it with flavor and colour. The city’s population in 1952 was estimated at 62,000, of which more than half were non-indigenes. A traditional ruler who witnessed the coal era boom, testified that virtually every family in Enugu had at least one member working at the Corporation and that the mines had a large dependent economy. Later, when crude oil took over from the revenue derived from coal, its impact was less felt on a national scale.

While the benefits of the coal mines were largely economical and immediate, it also had negative and long term effects, especially on the environment. These effects are particularly compounded by the failure of the government to reclaim most of these mines – especially those abandoned during the civil war. Enugu state is reputed to have the worst erosion in the entire nation – a condition attributable to unreclaimed mines and unregulated artisanal mining at abandoned mine sites throughout the state. A study by the Journal of Environmental Science and Technology on the effects of mine drainage on water bodies, specifically looking at coal mining in Enugu concluded that “the quality of the water is significantly influenced by acidic mine drainage and its impact on human health could be severe.” There are currently over 22 redundant coal mines around Nigeria, four of which were fully developed coal mines. There is no coherent public discussion about their existence or more importantly, their reclamation. With such a rich and varied history of coal, it’s about time Nigeria has a well informed debate about its energy future.

Abiodun Baiyewu is the Country Director at Global Rights Nigeria, from where she directs the organisation's Natural Resources and Human Rights Program. She has worked with community organizations in Nigeria including the Negotiation and Conflict Management Group, the Center for African Policy and Peace Strategy, and the American Center for International Labor Solidarity. She is an alum of the Georgetown University Law Center in Washington D.C., where she was also a Women's Law and Public Policy Fellow in the Leadership and Advocacy for Women in Africa Program. In addition she is an accredited mediator, dispute resolution trainer, and an HIV/AIDS youth counselor.

Abiodun Baiyewu is the Country Director at Global Rights Nigeria, from where she directs the organisation's Natural Resources and Human Rights Program. She has worked with community organizations in Nigeria including the Negotiation and Conflict Management Group, the Center for African Policy and Peace Strategy, and the American Center for International Labor Solidarity. She is an alum of the Georgetown University Law Center in Washington D.C., where she was also a Women's Law and Public Policy Fellow in the Leadership and Advocacy for Women in Africa Program. In addition she is an accredited mediator, dispute resolution trainer, and an HIV/AIDS youth counselor.